Our Climate is Changing, Why aren’t we?

Getting Started Using Children’s Literature.

Overview

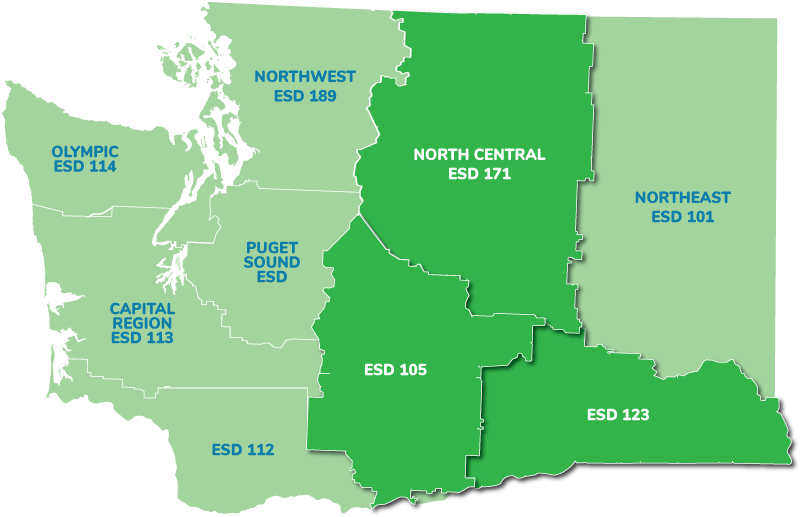

During the 2022-2023 school year, Educational Service Districts 105, 123 and 171 partnered to launch a climate science-centered book study, hosting a cohort of 55 educators primarily located in eastern Washington. During these sessions, educators were able to deepen their own understanding of climate change as well as have dedicated time to strategize around integrating children’s literature about climate change into their curriculum. Participants workshopped age-appropriate ways to integrate climate science in a way that centers a variety of perspectives, including hearing directly from two authors about the Indigenous perspectives and teachings they carry from their communities.

What We Did

Professional Development: The book study, Our Climate is Changing, Why Aren’t We? Getting Started Using Children’s Literature, consisted of four professional development sessions. During these sessions, participants reviewed diverse and age-appropriate climate science literature for their classrooms, learned new ways to integrate Common Core and Next Generation Science Standards through literature, and brainstormed ways to inspire student agency throughout. Each professional development session was centered around texts to use in the classroom, including This is Climate Change, Mario & the Hole in the Sky, The Tantrum That Saved the World, Our World Out of Balance, Old Enough to Save the Planet, If Polar Bears Disappeared, and The Whale Child.

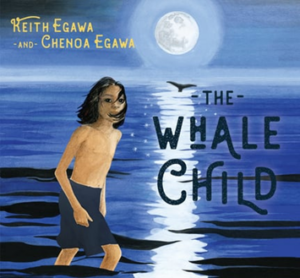

Engaging with the Authors: The third session featured The Whale Child, authored by sibling duo Chenoa and Keith Egawa from Lummi Nation. The Egawa’s helped facilitate the professional development session featuring their book, creating an opportunity to center Indigenous perspectives and teachings as they relate to climate and the natural world. This collaboration created an important opportunity to expand perspectives on climate science and highlight the teachings and experiences of the original stewards of the land.

Engaging with the Authors: The third session featured The Whale Child, authored by sibling duo Chenoa and Keith Egawa from Lummi Nation. The Egawa’s helped facilitate the professional development session featuring their book, creating an opportunity to center Indigenous perspectives and teachings as they relate to climate and the natural world. This collaboration created an important opportunity to expand perspectives on climate science and highlight the teachings and experiences of the original stewards of the land.

Chenoa shared: “For me…nature is saying you need to recognize I’m a part of you and you’re a part of me. We’re not separate and none of us are separate. We’re all breathing the same air… drinking the same water. It’s really seeing the humanity that we each share and that there’s a wealth and a diversity of our knowledge… All of us have teachings that are important, and we’re all needed at the table”

What We Learned

Indigenous Knowledge in the Classroom

Authors Keith and Chenoa invited educators to think about what it means to have inclusion of Indigenous wisdom in climate science curriculum: “Native teachings offer thousands of years of observations, of [our] connectedness and dependence on the natural world…” Chenoa encourages educators to make time for students to hear from a wealth of diverse cultural perspectives. The authors ask educators to center humanity into science education, something that can sometimes be lost among the standards.

Through The Whale Child, students can see the importance of their reconnecting to the natural world. Chenoa reflects, “[we are part of the] web of life that is all intricately interrelated, our actions, words, what we are doing in our life is affecting not just us and our immediate surroundings, but the whole world.” Their hopes for The Whale Child and for climate science curriculum are to empower student agency and inspire lifestyle changes among youth for the wellness of our environment.

Seeing Themselves in the Text

Seeing Themselves in the Text

ClimeTime regional science coordinators emphasized the importance of having a curriculum where students see themselves in the texts they study. A book study participant and fifth grade educator noted that her students showed a sense of pride when reading the book study text, Mario & the Hole in the Sky. In the text, author Elizabeth Rusch explores the life and achievements of Mexican chemist, Mario Molina. This teacher described how in her class, where a majority of students are Spanish-speaking and identify as Latinx, students felt hope and pride in their heritage being centered in the curriculum. The teacher observed that readings like this made students see that they could be someone who goes out into the world and have an impact, remembering the “sense of pride… they saw somebody like them… who had gone and done these great things. So, I thought that was really inspiring”

Ongoing Partnerships

Participants of the book study sessions expressed the desire to share climate science resources with their peers, principals, and district curriculum specialists. At the same time as many educators across the state are facing resistance from community members, teachers involved in the program recognize the pressing need to educate students about environmental changes. One educator described the desire to embed texts like The Whale Child in their newly adopted ELA curriculum, integrating the content areas to foster a generation of environmentally conscious and informed students.

Additionally, Chenoa and Keith are eager to continue ongoing collaboration with OSPI, the “Since Time Immemorial” curricula development, and the ClimeTime initiatives to enhance climate science curriculum from a humanistic lens, one that places the heart at the center of the work: “You have family on land as you do in the sea… being a caretaker of the earth begins with taking care of the water that all life depends on.”

Project Reach

Teachers & Coaches

Project Partners

Contact

Lorianne Donovan-Herman

Regional Science Coordinator

ESD 123

ldonovan@esd123.org